Plant mediated insect interactions

- How do foliar and floral chemical traits alter insect behavior, and how do interactions with insects alter plant chemistry in different tissues? How does plant chemistry mediate interactions between herbivores and pollinators?

The adaptive role of specialized necar chemistry

- How does specialized milkweed nectar chemistry alter pollinator behavior and plant fitness?

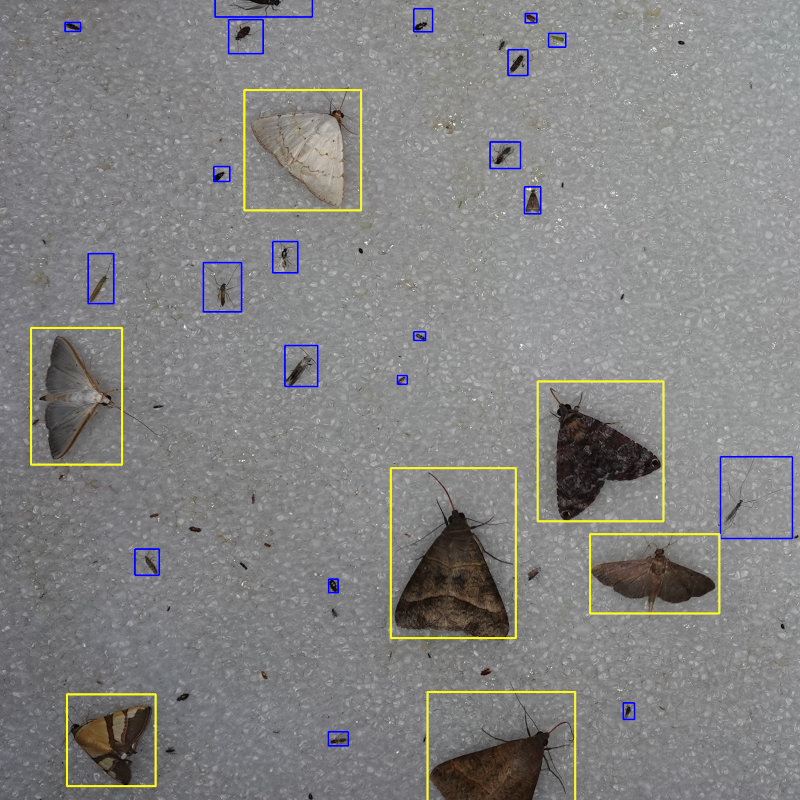

Using computer vision for automatic insect surveys

- How can machine learning facilitate surveys of biodiveristy and insect behavior in the field?

-

Publications

-

* Indicates preprints

- A. Grele and L. Richards. 2026. BugNet: a rapid and scalable pipeline for automated insect monitoring using hierarchical data. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 14:1750931.

- L. Martinez, N. C. Aflitto, F. T. MacNeill, A. Grele, J. S. Thaler. 2025. A predator pheromone increases potato yield through multiple mechanisms involving plant and prey responses Journal of Economic Entomology 118 (3), 1297-1306

- A. Grele, T. J. Massad, K. A. Uckele, L. Dyer, Y. Antonini, L. Braga, M. L. Forister, L. Sulca-Garro, M. Kato, H. G. Lopez, A. R. Nascimento, T. Parchman, W. R. Simbaña, A. M. Smilanich, J. O. Stireman, E. J. Tepe, T. Walla, and L. Richards. 2023. Intra and interspecific diversity in a tropical plant clade alter herbivory and ecosystem resilience. Elife 12, RP86988.

- Massad, T., A. R. Nascimento, D. Campos, W. Simbaña, H. G. Lopez, L. S. Garro, C. Lepesqueur, L. Richards, M. Forister, J. Stireman, E. Tepe, K. Uckele, L. Braga, T. Walla, A. Smilanich, A. Grele, and L. Dyer. 2023. Variation in the strength of local and regional determinants of herbivory across the Neotropics. Oikos, e10218

- Getman‐Pickering, Z. L., A. Campbell, N. Aflitto, A. Grele, J. K. Davis, and T. A. Ugine. 2020. LeafByte: A mobile application that measures leaf area and herbivory quickly and accurately. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11:215–221.

-

Presentations

-

* Indicates posters, † indicates talks

- A. Grele, L. Richards. 2025. More than sugar water: Specialized nectar chemistry as a driver of pollinator behavior and competition. Entomological Society of America.

- A. Grele, L. Richards. 2025. Not all pollinators are equal: Specialized nectar chemistry alters plant fitness by selectively modifying insect behavior.. HCCE annual symposium.

- A. Grele, L. Richards. 2024. Nectar chemistry alters plant fitness by manipulating pollinators. Entomological Society of America.

- A. Grele, L. Richards. 2024. Chemical signals and chemical noise - why plant defenses are more complex and pheromones are simpler in the tropics. 27th International Congress of Entomology.

- A. Grele, L. Richards. 2024. Intra- and interspecific variation in milkweed nectar chemistry. HCCE annual symposium.

- A. Grele, C. Mallon. 2024. Raman Spectroscopy at a Distance: A Tool for Ecological Research in the Field. HCCE annual symposium.

- A. Grele, L. Richards. 2023. Simulated herbivory increases plant fitness by altering floral traits and pollinator behavior. Gordon Research Conference.

- A. Grele, L. Richards. 2022. Using machine learning to study pollination with high temporal and taxonomic resolution. Entomological Society of America.

- A. Grele, N. C. Aflitto, J. S. Thaler. 2018. Species-specific responses of the Colorado potato beetle to pheromone cues of predatory and phytophagous pentatomids. Entomological Society of America.